Caribbean History

Indigenous Peoples of the Caribbean: A History

The Caribbean region, known for its stunning beaches and vibrant cultures, was once home to thriving Indigenous societies long before the arrival of Europeans in the late 15th century. These early inhabitants, including the Taíno, Kalinago (Caribs), and Guanahatabey, shaped the cultural, social, and ecological landscapes of the islands. Understanding their history is crucial to appreciating their contributions and the challenges they faced during and after colonization.

Origins and Migration

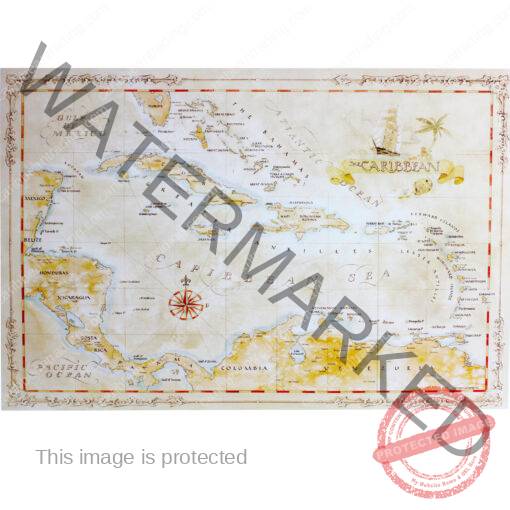

The first Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean arrived thousands of years ago, tracing their origins to South America. Archaeological evidence suggests that these groups traveled by canoe, navigating the waterways of the Orinoco River and the Amazon Basin before reaching the islands. The earliest settlers, known as the Archaic or Pre-Ceramic peoples, arrived around 4000 BCE. They were hunter-gatherers who relied on fishing, hunting, and foraging for their survival.

By approximately 500 BCE, a second wave of migrants, the Saladoid people, introduced agriculture, pottery, and more complex social structures to the Caribbean. Originating from the Orinoco Valley, they cultivated crops like cassava, maize, and sweet potatoes, and their pottery featured intricate designs. The Saladoid culture laid the groundwork for the societies that would later become the Taíno.

The Rise of the Taíno

The Taíno, one of the most well-documented Indigenous groups of the Caribbean, flourished during the late Pre-Columbian period. They inhabited islands such as Hispaniola (modern-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic), Puerto Rico, Jamaica, Cuba, and the Bahamas. Organized into chiefdoms, or cacicazgos, the Taíno society was hierarchical, with caciques (chiefs) leading political and religious affairs.

Their culture was rich and deeply spiritual. The Taíno worshipped deities known as zemis, which were believed to influence natural phenomena, health, and prosperity. They created ritualistic artifacts, including stone and wooden idols, to honor these gods. Their ceremonial centers, marked by petroglyphs, stone plazas and ball courts, served as sites for communal gatherings, games, and spiritual practices.

The Taíno excelled in agriculture, cultivating staples such as cassava, a drought-resistant crop that remains an essential part of Caribbean cuisine today. They also practiced sustainable fishing and hunting techniques, which helped maintain a balance with the natural environment.

The Kalinago: Masters of Resistance

Another prominent Indigenous group in the Caribbean were the Kalinago, also known as the Caribs. The Kalinago inhabited the Lesser Antilles, including islands like Dominica, Saint Lucia, and Grenada. Known for their seafaring skills, they built sophisticated canoes that enabled them to travel across vast distances.

Unlike the Taíno, the Kalinago were perceived by European colonizers as fierce warriors. They had a reputation for defending their territories against intruders, both Indigenous and foreign. This resilience allowed them to maintain relative autonomy in the early years of European contact.

The Kalinago society was less centralized than that of the Taíno, relying on smaller, more flexible communities. They practiced a mix of subsistence agriculture, fishing, and raiding neighboring islands for resources. Their spiritual beliefs, like those of the Taíno, were deeply rooted in nature and ancestral reverence.

The Impact of European Colonization

The arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492 marked the beginning of a catastrophic era for the Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean. Within decades, their populations were decimated by a combination of violence, enslavement, and diseases such as smallpox and measles, to which they had no immunity.

The Spanish encomienda system, which forced Indigenous peoples into labor under brutal conditions, further accelerated their decline. The Taíno, in particular, were subjected to widespread exploitation, and their numbers plummeted from an estimated hundreds of thousands to a few hundred within a century of contact.

The Kalinago, though initially more resistant to European encroachment, also faced severe challenges. French and English colonizers waged wars against them throughout the 17th century, culminating in the loss of their lands and autonomy.

Cultural Survival and Legacy

Despite the devastation wrought by colonization, the legacy of the Caribbean’s Indigenous peoples endures. Their languages, customs, and agricultural practices have left an indelible mark on the region’s cultural identity. Words of Taíno origin, such as “hammock,” “canoe,” and “barbecue,” are now part of global vocabulary.

Traditional foods, including cassava bread and pepper sauces, remain staples in Caribbean cuisine. Indigenous agricultural techniques, such as intercropping, continue to influence sustainable farming practices. Additionally, many Caribbean cultural expressions, from music to spirituality, reflect the syncretism of Indigenous, African, and European traditions.

Modern descendants of the Kalinago, primarily based in Dominica, continue to preserve their heritage. The Kalinago Territory, established in 1903, serves as a self-governed community where they maintain traditional crafts, ceremonies, and storytelling. In Puerto Rico, efforts to reclaim Taíno identity have gained momentum, with many people embracing their Indigenous ancestry. You can see a lot of Taíno accessories being sold all around the island, as well as from other parts of the world, such as those found in an Indian decor store, African artisan stalls and more.

Rediscovering the Past

Ongoing archaeological research and historical scholarship are shedding new light on the lives of the Caribbean’s Indigenous peoples. Advances in DNA analysis have revealed that traces of Taíno ancestry persist in the genomes of modern Caribbean populations, disproving earlier claims that they were entirely “extinct.”

Cultural revitalization movements across the region are also working to reclaim Indigenous heritage. Museums, educational programs, and festivals celebrate the contributions of the Taíno and Kalinago, ensuring that their stories are not forgotten.

Challenges and the Future

While efforts to honor Indigenous Caribbean history have grown, challenges remain. The narratives of colonization often overshadow the achievements and resilience of these societies. Additionally, descendants of Indigenous peoples face systemic inequalities, including limited access to resources and political representation.

Recognizing and addressing these issues is essential for fostering a more inclusive understanding of Caribbean history. This includes supporting Indigenous-led initiatives and promoting the teaching of pre-Columbian history in schools.

Conclusion

The Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean were pioneers of navigation, agriculture, and culture in the region. Their societies, though profoundly affected by European colonization, have left a lasting legacy that continues to shape the Caribbean’s identity. By rediscovering and preserving their history, we can pay homage to their contributions and ensure that their stories endure for generations to come.